Written by Mason Vander Lugt, Syracuse University catalog librarian and proprietor of the historical music blog Dinosaur Discs.

After experimenting with Irish comic-dramas on stage between 1891 and 1895, and his successful theatrical production of The Wizard of Oz in 1902, L. Frank Baum took the Oz franchise in a wonderful (if ill-fated) direction with the “Fairylogue and Radio-Plays” in 1908.

Leveraging the current taste for the exotic, Baum named the first part a “Fairylogue” after the increasingly popular “Travelogue”. The Chicago Tribune described it as follows –

A fairylogue is a travelogue that takes you to Oz instead of China… A radio play is a fairylogue with an orchestra on the left-hand side of the stage

If you’re familiar with media history, you may wonder why Baum would put on a “radio play” more than a decade before consumer radios began to sell in the United States. Baum called the multi-media theatrical production a “radio play” to invoke the energy behind the developing technology despite a complete absence of any radio-broadcast technologies. He later justified the name by stating that the process used to color the glass photo-slides was invented by a Parisian named Michel Radio, though there’s no further evidence of this person having existed (the slides were actually colored by the Duval Frères company.

Even if he didn’t have the terms quite correct, Baum was certainly ambitious in his use of developing technologies to present a fantastic experience to his viewers. At the beginning of the show, the author would walk on stage in a “lily-white suit” to introduce the characters, then walk off to one of the wings, hiding behind a velvet curtain, while he was replaced by a film projection of himself, in the same suit, among the characters and scenes of Oz. He would remain onstage to narrate the events, as sound-films were not yet available.

The first act of the show combined scenes from the first Oz books, and the second continued into scenes from John Dough and the Cherub. It combined motion picture, painted backdrops, ‘magic lantern’ style hand-colored slide projections, live orchestra, special effects, and, of course, live narration by the author. It was a spectacle. Audiences loved it.

Admission, however, averaged $3 – twelve times to cost of the average theater ticket at the time. Commercially, the Fairylogue and Radio-Plays were a disaster. Baum had personally funded the project, and convinced the owner of the Selig Polyscope film company of Chicago to produce the film segments under a promise of later payment. The production only lasted three months, and most of the nationally-scheduled dates were cancelled because of the high overhead costs. Baum’s biographer called the Fairylogues a “significant contributing factor” to his bankruptcy claims three years later.

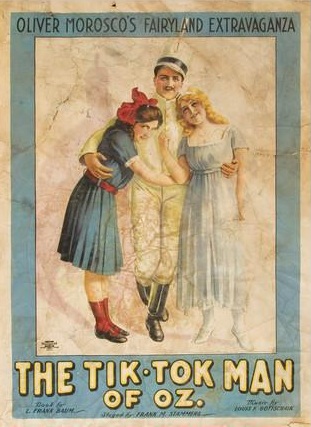

This was only an inconvenience to the determined author. In 1913, he opened “The Tik-Tok Man of Oz”, with music by Louis Gottschalk, at Geo. M. Cohan’s Grand Opera House in Chicago.

This post was assembled from notes held in the L. Frank Baum papers at the Special Collections Research Center of the Syracuse University Library. The collection holds biographical information of the Baum and Gage families, typescripts of his written works, correspondence between Baum and his publisher, playbills, photographs, memorabilia and more. If you have any research interest in Baum’s life or work, please contact the Research Center.