Written by Mason Vander Lugt, Syracuse University catalog librarian and proprietor of the historical music blog Dinosaur Discs.

Many historians are content to describe the invention of the phonograph as a flash of inspiration on a single day in Thomas Edison’s New Jersey laboratory in July of 1877. While he may have been the ‘wizard of Menlo Park’, Edison was only a man (if an uncommonly gifted and dedicated one). The recording and reproduction of sound had been theorized and predicted for centuries, and scientific breakthroughs in acoustics of the 19th century made it a matter of time.

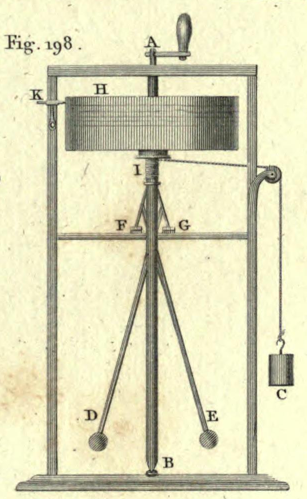

Thomas Young, in his 1807 Course of Lectures on Natural Philosophy and the Mechanical Arts, describes a ‘vibrograph’ used to measure the frequency of a sounding body (read: tuning fork) by etching the vibration of the fork into the surface of a soot-covered cylinder. The weights, labeled D and E regulate speed, a feature that would remain on most mechanical phonographs. The cylinder fell down the axis as the cord, labeled I, unwound.

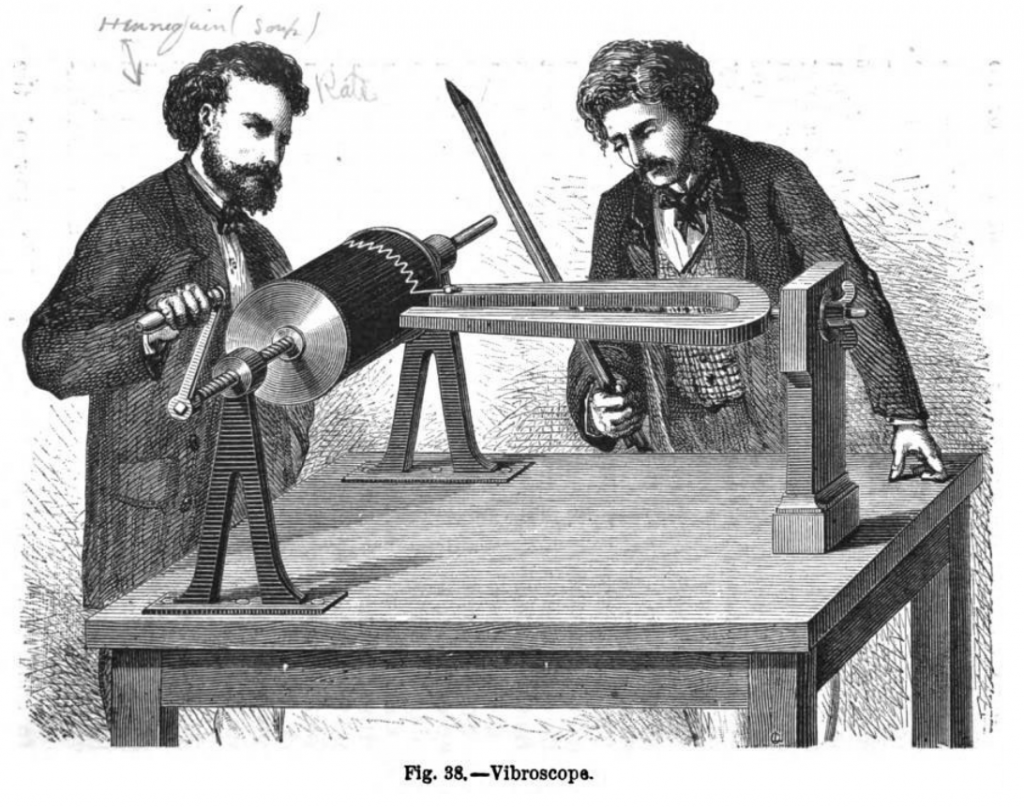

In 1843, Jean-Marie-Constant Duhamel independently designed the “vibroscope,” which moved the cylinder laterally using of a feedscrew, a feature of the first generation of phonographs.

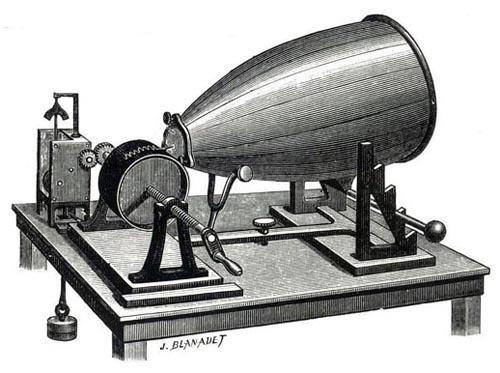

Leon Scott introduced a breakthrough in 1857 by replacing the tuning fork with a bristle attached to a pliable membrane capable of vibrating in correspondence with sounds in the air. Though Scott didn’t intend for his phonautograph recordings to be reproduced, he must have understood the possibility. In 2008 sound researchers (or archeophonists) reproduced these inscriptions by optically scanning the sheets and digitally reconstructing the waveforms held within.

Edison’s ‘flash’ of inspiration occurred when he was working on a high-speed telegraph transmitter. The device indented morse code into a taut length of paper tape, and Edison likened the sound to ‘human talk heard indistinctly’. He had been working on improvements to Alexander Graham Bell’s nascent telephone, and wondered if a telephone message could be recorded in the same way as a telegraph message.

On July 18 of 1877, he successfully recorded his voice using the carbon diaphragm of his telephone receiver and an embossing point against wax paper, noting:

“The speaking vibrations are indented nicely, and there’s no doubt that I shall be able to store up and reproduce automatically at any time the human voice perfectly”

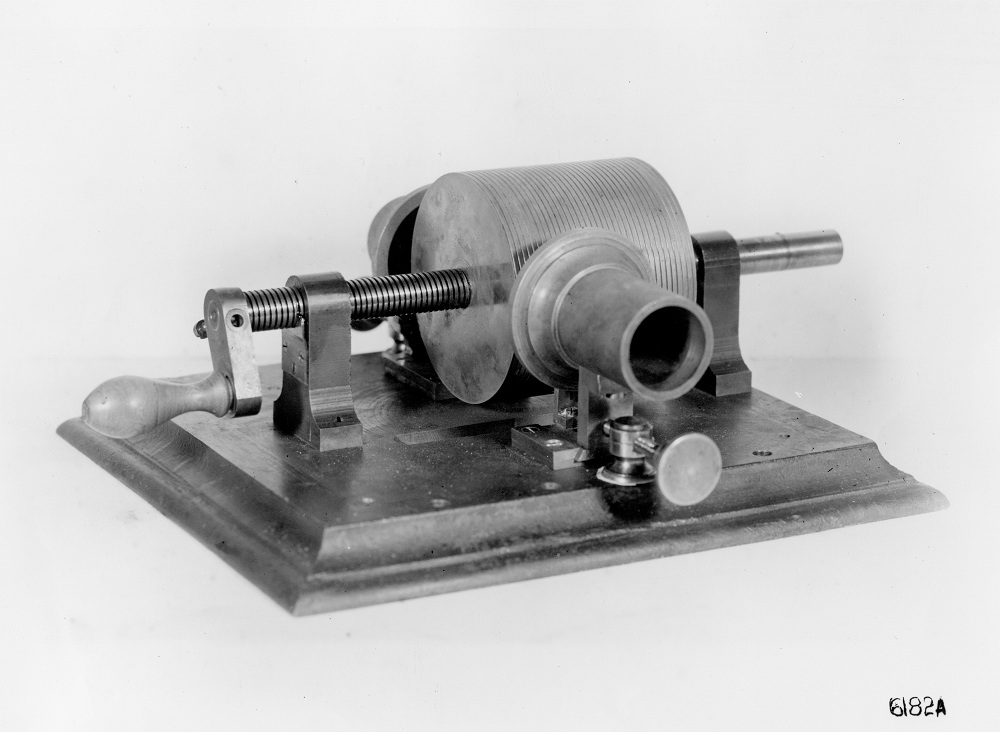

Though Edison gave the date of his first successful foil recording session (the fabled recitation of ‘Mary had a little lamb’) as August 12, Roland Gelatt provides compelling evidence in “The Fabulous Phonograph” that the machine used to make this recording wasn’t manufactured until November 29th.

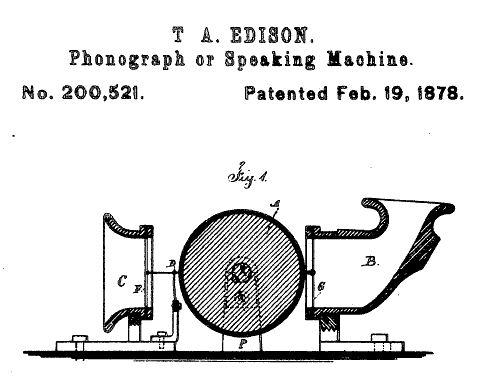

The term ‘phonograph’ had been applied to at least two previous, virtually unrelated, inventions (by the Pitman brothers in 1837 to describe a form of phonetic ‘shorthand’ writing and by F.B. Fenby in 1863 to describe a sort of proto piano-roll recorder). A French poet name Charles Cros also conceived of a phonograph in 1877 that was virtually Edison’s equal in purpose, but never realized it. Edison was probably unaware of Cros’ work, and predictably named the device after the Greek ‘sound-writer’, in the prevailing style of the telegraph and telephone.

In December 1877, Edison exhibited the phonograph in the office of Scientific American magazine, drawing a crowd so large that the editor had to halt the demonstration because the room was beyond capacity. Word of the invention spread quickly through the local press in the weeks to come. In January 1878, before the patent on the device had been guaranteed, Edison sold the manufacturing rights for the device to the Edison Speaking Phonograph Company. The company manufactured approximately five hundred units of the crude instrument before Edison followed an investment opportunity into the development of the incandescent light bulb, effectively abandoning the phonograph.

Fortunately, one of the buyers of the parlor foil phonographs had big ideas for further development. In 1880, Alexander Graham Bell won the Volta Prize of $10,000 from the French government for his invention of the telephone. Bell used this money to set up a laboratory in Washington DC for further electrical and acoustical research.

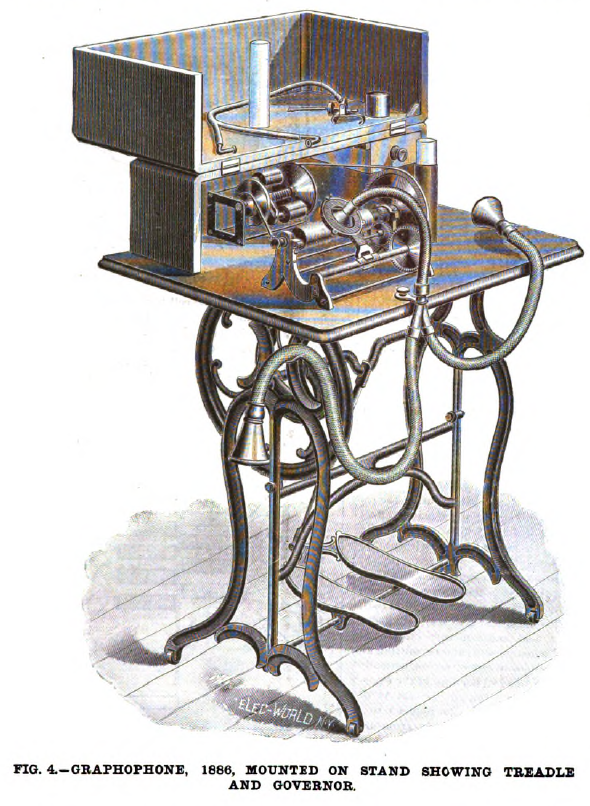

Bell, along with his associates Charles Sumner Tainter and cousin Chichester Bell, experimented with a variety of technologies between 1880 and 1886, but found Edison’s design, with some small but significant adjustments, to be the best approach. Realizing their predicament, Bell and co. approached Edison to propose a partnership for continued development and marketing. Whether for profit, legacy, or simply competition, Edison refused their offer and resumed development of the phonograph, founding the Edison Phonograph Company in 1887. The next year, Edison debuted his “improved” and “perfected” phonographs, using the engraved wax medium and mobile reproducer developed by the Volta laboratory.

Bell and co. were determined to succeed, and incorporated Volta Graphophone in February 1886. They filed several patents that would guarantee their success in both the cylinder and disc phonograph markets that now seemed destined for greatness. Chief among these was the specification that recordings be engraved, or cut, into the surface of the recording medium, rather than Edison’s specification of embossing, or impressing, the recording, which only held for foil.

In the summer of 1888, civil war veteran and glass magnate Jesse H. Lippincott became interested in the financial potential of the technology as a dictation machine, and invested hundreds of thousands of dollars to consolidate the American Graphophone Co. (successor to Volta Graphophone) and the Edison Phonograph Co. Lippincott’s limited vision for the machine, along with high costs, complicated leasing arrangements, and opposition from stenographers (whom the machines were intended to replace), doomed the company, and Lippincott sold out to Edison in the fall of 1890.

Edison’s purchase of North American at this time was a wild stroke of luck on his part. Though he had decided to sell the machines outright, he had come to loathe the idea of selling phonographs for entertainment, preferring their ‘practical’ use in the office. A California businessman named Louis T. Glass disagreed.

Along with his business partner William S. Arnold, Glass designed, built and patented a coin-actuated phonograph, and had begun demonstrating its value as a public entertainment machine (a jukebox, in effect, though he wouldn’t use this word) to great acclaim. Despite Edison’s outspoken discouragement of this trend, the small cylinder manufacturing outfits that emerged to supply the North American Phonograph Company followed the money and began marketing pre-recorded entertainment cylinders. Without this fortunate turn, Edison’s North American would probably have continued on the same path as Lippincott’s. The battery powered “Class M” phonographs were simply too expensive, too complicated, and unreliable. Glass’s clever appropriation breathed new life into a withering industry.

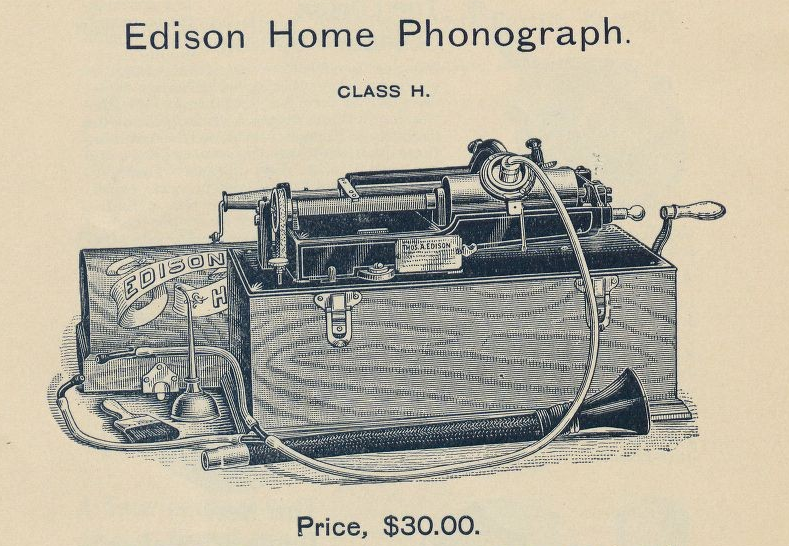

Edison, always the pragmatist, sanctioned the production of entertainment cylinders in late 1890 and turned his attention to perfecting the phonograph machines. In 1894, he declared bankruptcy for the North American Phonograph Company and bought back exclusive rights to his patents. In 1896, he founded the National Phonograph Company to market his new spring-motor home phonographs and entertainment cylinders.

The Columbia Phonograph Company, under the direction of Edward Easton, had been producing entertainment cylinders under North American’s nose for a year prior to Edison’s assent. This head start would give them an advantage in what would become a competitive and lucrative business. Between 1893 and 1895, Easton went on to negotiate a merger with the failing American Graphophone company whereby Columbia Phonograph would produce recordings, and American Graphophone would market their machines under the newly prominent Columbia brand. Edison acknowledged this threat, and patent battles in the next two years began to burden both. Recognizing their legal stalemate and the futility of costly litigation, Columbia and National cross-licensed the fundamental technical patents in December 1896.

1897 marks the beginning of a mature home phonograph market, with both Columbia and National selling machines and records. Competition between the two firms quickly drove down prices for home players, but technical limitations still limited the potential for profit. The recordings were still quiet, low fidelity, and too short to hold popular songs (two minutes), but most importantly, the inability to duplicate the recorded cylinders meant that companies must be constantly recording, and performers must be constantly performing if they were to keep pace with demand. The emerging disc market had solved this by introducing a metal ‘master’ recording that could stamp the impression into a shellac disc, but this was fundamentally impossible for a cylindrical carrier. Edison and Columbia briefly employed a pantograph for duplication between 1898 and 1902, but its scale was limited.

Columbia gradually phased out cylinder operations in favor of discs beginning in 1901, halting production in 1909, and phasing out the subsidiary Indestructible cylinders in 1912. Edison spent the same period perfecting the cylinder. In 1898 they debuted a larger concert cylinder to increase loudness. In 1902, they began marketing Gold Moulded records, which were mass-produced by pressing the wax into a mold. In 1908 the wax Amberol increased recording time to four minutes, and in 1912, they debuted the celluloid Blue Amberol which was higher-fidelity and less prone to breakage. They debuted the Diamond Disc in the same year, but would continue selling the Blue Amberol cylinder line until they closed shop in 1929.

Treasures of Cylinder-Era Recording

All of this technology would mean nothing if it didn’t enable us to do something unprecedented and incredible, but it did. Cylinders have two distinct advantages over disc recordings. They existed earlier, and so were able to record sounds between their invention in 1877 and the beginning of a mature disc market around 1900 (Emile Berliner had technically been recording to disc since 1889, but this was a relatively minor operation). Wax cylinder recording was also available to the public like disc recording never was.

Julius Block was a Russian businessman who became fascinated by news reports of Edison’s phonograph in the late 1880s. He convinced Edison to give him a phonograph to bring back to Russia, and ended up recording a number of important musicians. Though these recordings were thought to be lost for decades, they were recently discovered in the Institute of Russian Literature in St. Petersburg. Many of these have been digitized, and some were released by Marston Records in 2008. The last track of this set is a funny conversation between pianist Anton Rubinstein, Julius Block, operatic mezzo-soprano Elizaveta Lavrovskaya, pianist and conductor Vasily Safonov and composer Pyotr Tchaikovsky. You can hear this recording here or read more about the collection here.

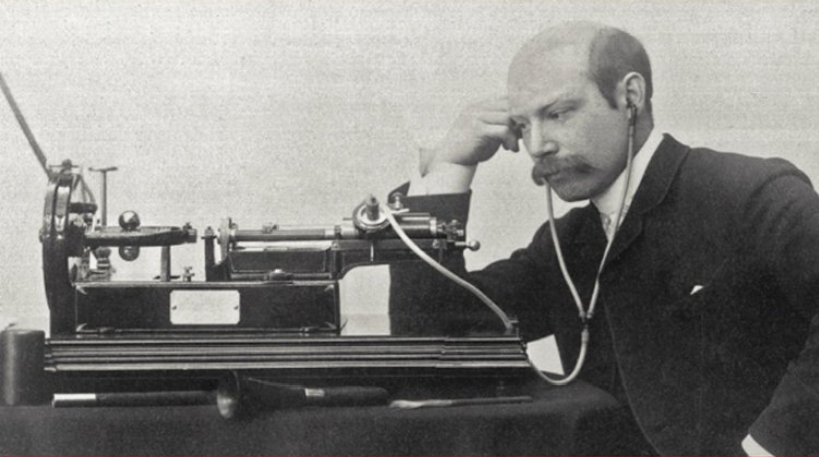

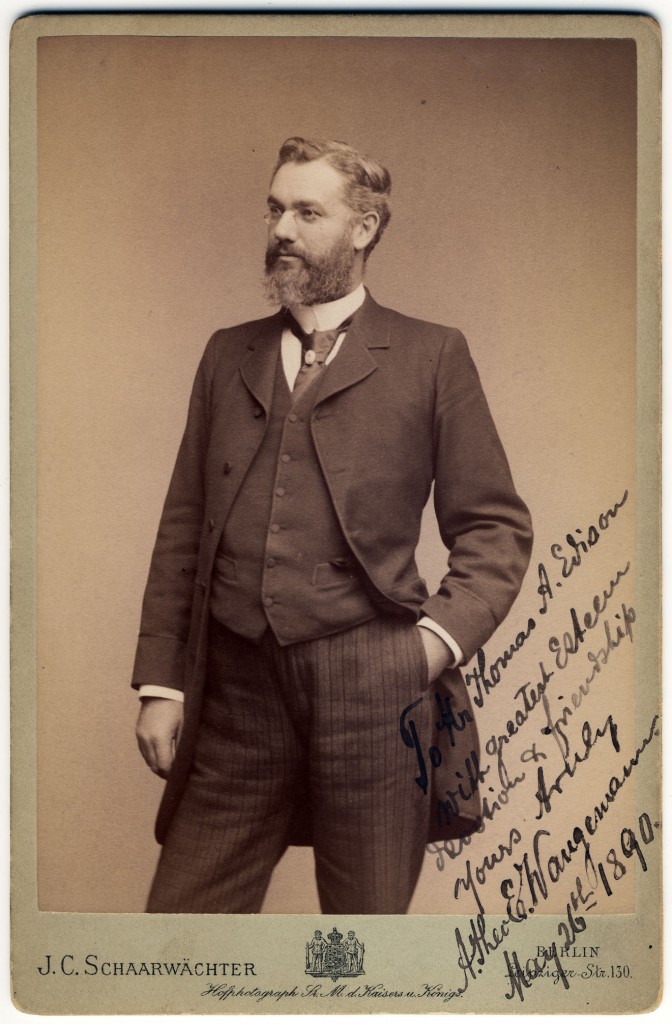

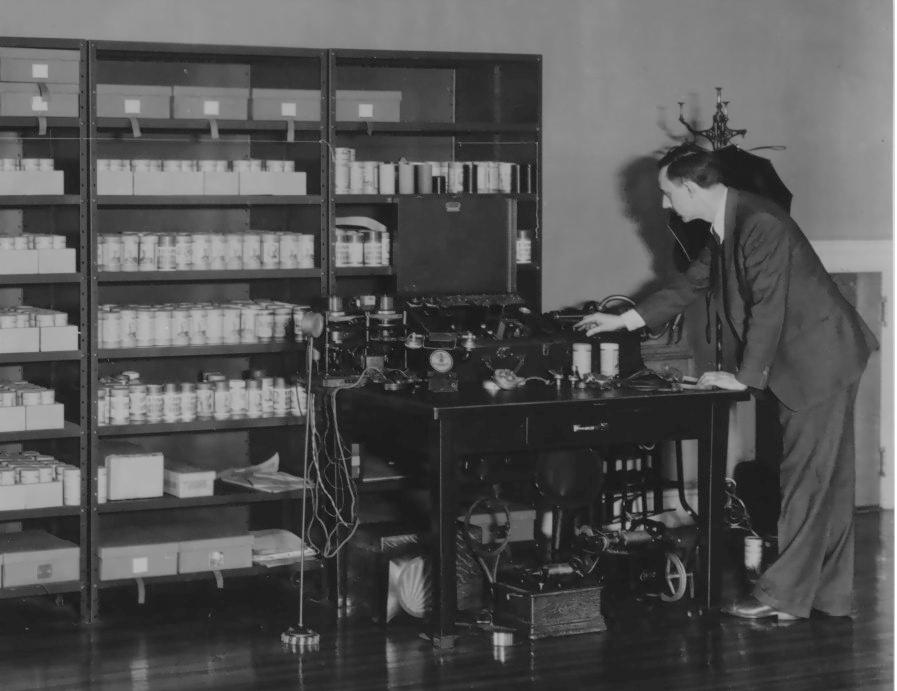

Theo Wangemann was Edison’s first sound recording engineer (and, by that merit, the first sound recording engineer). Edison sent Wangemann to Paris in June 1889 to demonstrate the machine at the Exposition Universelle, though he would stay in Europe until the next February traveling, demonstrating, and recording. Two of the great victories of this trip are recordings of Otto von Bismarck and Johannes Brahms. Many of these recordings can be heard at the website for the Thomas Edison National Historical Park.

Lionel Mapleson was the librarian for the Metropolitan Opera Company. His recordings, mostly made at the front of the live stage between 1900 and early 1904, captured a few great performers of the golden age of opera, some for the first or only time. Fortunately, the value of these recordings was understood from the beginning, and they have been studied, cared for and reissued with great care. The program notes for a 1985 LP reissue compiled by the New York Public Library’s Rodgers and Hammerstein Archive of Recorded Sound tells a history and provides audio examples [link].

Frances Densmore was a pioneer ethnographer and field recordist in the musical traditions of native Americans when society at large sought to assimilate or marginalize them. Most of her prolific recording legacy has not been transferred or reissued, but the original cylinders are still held at the Library of Congress.

Robert Winslow Gordon founded the Archive of American Folk Song in 1928. He was one of the first to realize the synthetic value of the folk traditions of American immigrant cultures, especially in the rural south. Aside from a 1978 LP (and its 2003 digital reissue), Gordon’s work has also had unfortunately little exposure.

Sources Consulted and Further Reading

The Fabulous Phonograph, by Roland Gelatt

From Tinfoil to Stereo, by Walter Welch, Oliver Read and Leah Brodbeck Stenzel Burt

The Patent History of the Phonograph, by Allen Koenigsberg

Tinfoil Phonographs, by René Rondeau