Written by Mason Vander Lugt, Syracuse University catalog librarian and proprietor of the historical music blog Dinosaur Discs.

We at Sound Beat are no strangers to conclusion. Ends of friendships, careers and lives are all in a day’s work, but the end of the world? That’s a special occasion. Speculation about how and when man will meet his eventual fate can be found in most cultures in history, but perhaps the last 60 years have been the most productive period of discussion and expression on the topic.

The prevailing model of the ‘end times’ in the west has been colored by a millennia-old account (purportedly a divine revelation) by John the Apostle. John envisioned an apocalyptic battle between the forces of good and evil that would provide artistic imagery for centuries to come. The account, which comprises the final book of the Christian bible, is complex and symbolic. Some characters and events, however, have stood out and become lasting icons in Christian art.

Majestas Domini pictures Christ in heaven, seated on a throne. The fourth chapter of John’s revelation describes Christ on a throne, surrounded by twenty four elders. This meeting begins the opening of seven seals guarding a scroll. The first four of these seals release the four horsemen, representing conquest, war, famine and death.

After the final seal is opened, seven angels appear, each holding a trumpet. As each of these trumpets is blown, another disaster befalls the earth. These include thunder and lightning, earthquakes, fire, seas of blood, and poisoned rivers. After the final trumpet is blown, a war commences in heaven, introducing a woman and child, a beast from the sea and another from the earth.

After more plagues and more judgements, the beast of the sea is joined by Babylon, who gains influence for the beast by seducing the kings of the earth.

The army of heaven, led by Christ on a white horse, with a sword coming out of his mouth, kills the armies of evil and Christ casts the two beasts into the lake of fire. After one thousand years in the abyss, Satan comes back to earth for one final battle. He is again defeated, and cast eternally into the lake of fire.

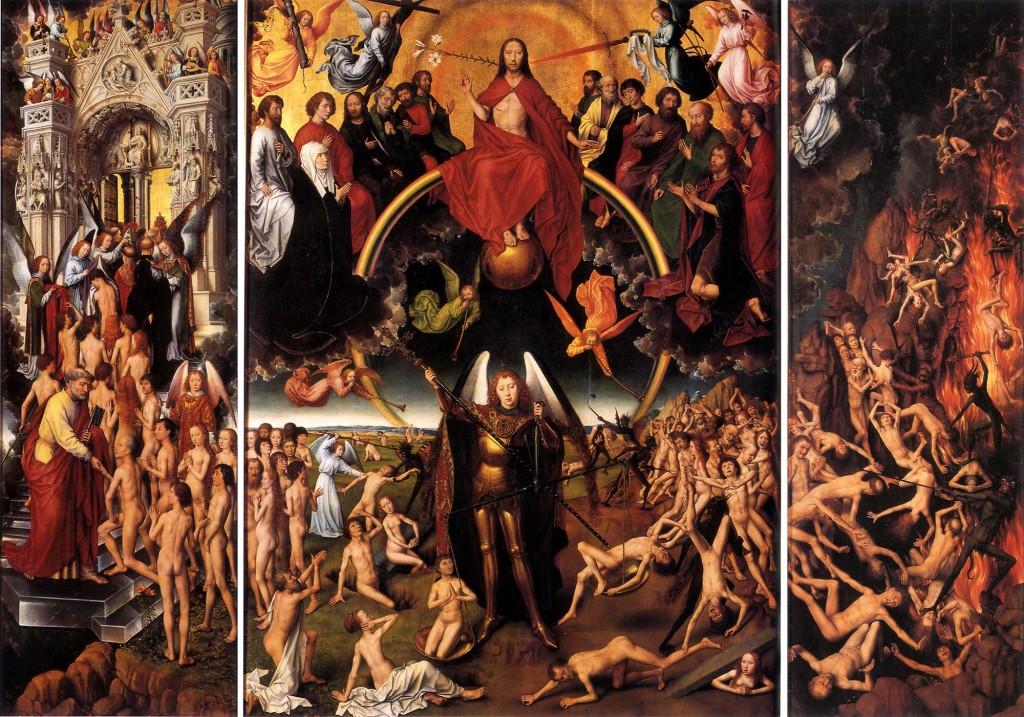

When this is complete, Christ raises the dead for one final judgement before destroying the heavens and earth and making new ones. JM Gates’ sermon ‘judgement day’ alludes to this last judgement. This event is seen as the culmination of all the events preceding it, and is probably the most popular scene in eschatological art. Many representations of the Last Judgment employ a triptych form with Christ, or archangel Michael, in the center, and heaven of hell on either side.

As scientific developments of the recent few hundred years have assuaged the fears of many of us (though not all) that a divine force will unexpectedly impose its apocalyptic will upon our kind, they have also created strange new theories and myths, and wonderful new modes of expressing them. As we have come to understand that any short term calamity will likely be of our own design, many expressions of the apocalypse have adopted a language of caution and choice.

On October 30, 1938, actor and radio producer Orson Welles delivered a memorable episode of his show Mercury Theatre on the Air, in which he adapted HG Wells’ War of the Worlds into a series of realistic-sounding radio news bulletins outlining a Martian attack on Earth. The reports of widespread violence and destruction caused by the Martians’ advanced technology captured the listeners’ attention and many believed the reports to be true. Science fiction and interest in space exploration boomed in the following years in children’s magazines and the novels of the futurians.

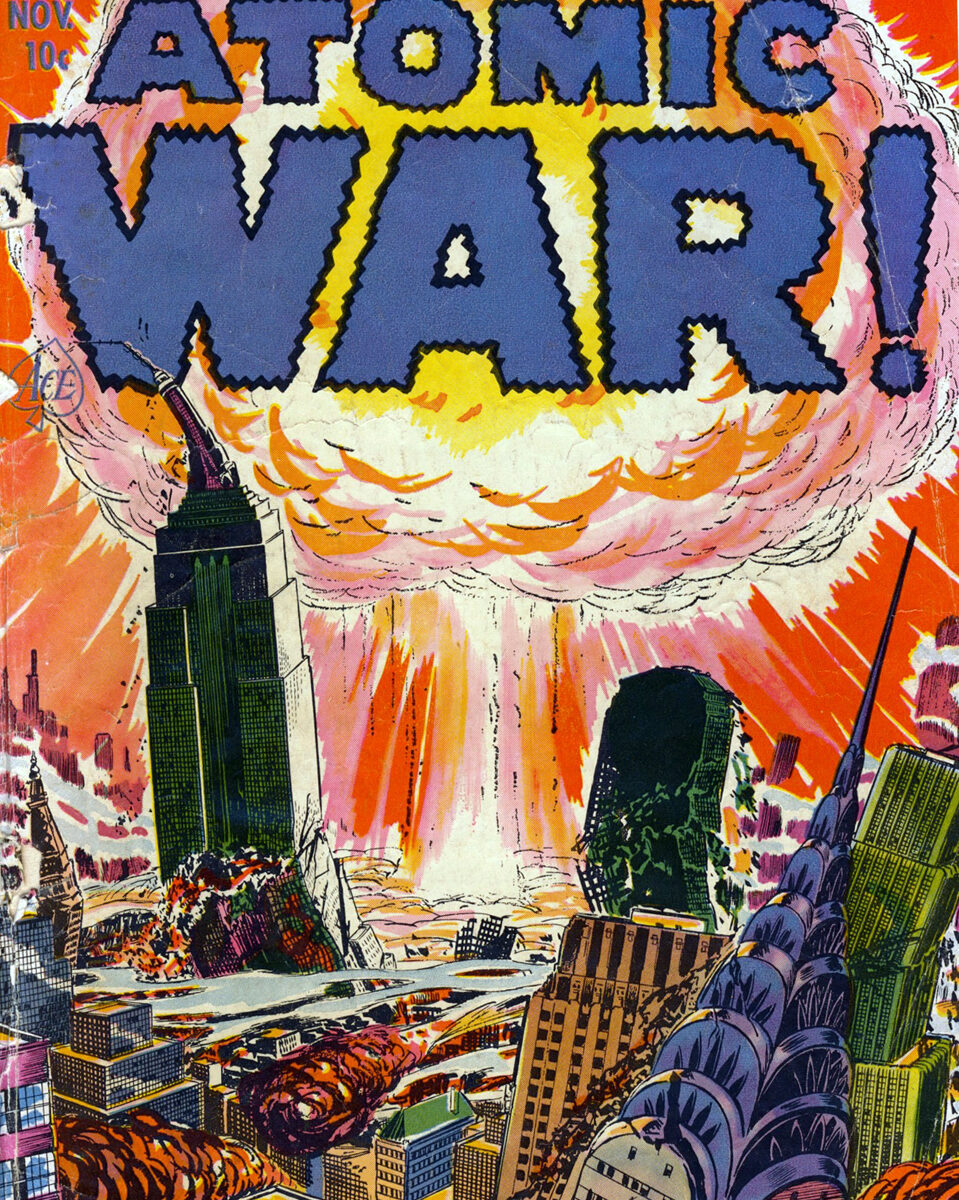

In the years following the second World War, tensions about nuclear armament and global war fueled a popular interest in what Susan Sontag called the “imagination of disaster”. Theories of World War III, nuclear apocalypse, and Communist imperialism incited works as diverse as Orwell’s cautionary novel Nineteen Eighty-Four and Duck and Cover, featuring Bert the Turtle.

In 1964, Stanley Kubrick elegantly summarized this culture of paranoia and propaganda in Dr. Strangelove. Dr. Strangelove theorizes a “Cobalt Thorium G doomsday machine” designed for mutually assured destruction in the case of any military attack. Once activated, the device can’t be disarmed. In theory, this ‘assurance’ would guarantee peace by making the option of attack self-destructive, but this, of course, falls apart if the enemy doesn’t know of its existence…

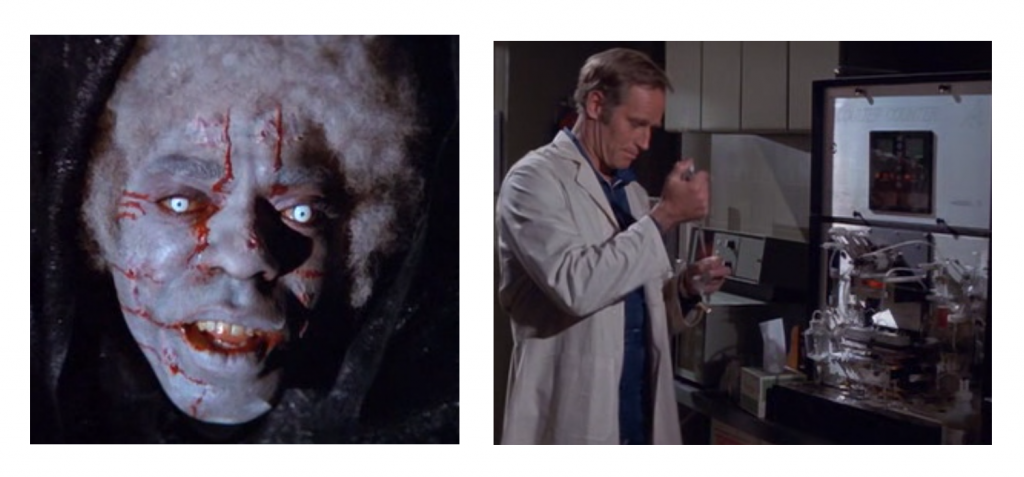

Four years later, George A. Romero took the threat of nuclear radiation in a wholly unexpected direction with Night of the Living Dead. As this week’s episode Zombies! suggests, human reanimation was not invented by Romero, but he did create a memorable archetype that would inform zombie flicks to the present day. In Night of the Living Dead, a radio newscast explains that radioactive fallout from a spacecraft destroyed in re-entry is to blame. In subsequent myths, hell has run out of space, science has meddled with the affairs of the church, and a rage inducing virus has spread.

The last of these was probably influenced by Boris Sagal’s 1971 The Omega Man. Based on Richard Matheson’s 1954 novel I Am Legend, The Omega Man features Dr. Col. Robert Neville (Charlton Heston) as one of the last survivors of a war-born virus that has killed most of humanity, and turned the survivors into murderous monsters. In the following decades, Outbreak (1995) and Contagion (2011) made pandemics scary without invoking humanoid antagonists.

Recently, films have begun to deal with the possibility that climate change will make the earth uninhabitable to human life. Though narrative drama requires an abridged timescale compared with real environmental projections, the almost inevitable reality of the underlying concept makes it very frightening material indeed. I can’t recommend The Day After Tomorrow, but it’s 2004 release date makes it the first major film to successfully confront this topic, two years before Al Gore’s influential book and movie An Inconvenient Truth. Five years later, the same director debuted 2012, in which ‘solar radiation’ (picking up on a theme here?) tenuously provokes a number of simultaneous globally catastrophic weather events.

These movies (and magazines, and radio dramas…) are designed for entertainment, and shouldn’t be taken too seriously, but their increasing success shows that audiences have embraced two things: a morbid curiosity, and a global kinship. As humanity faces global challenges real and imagined, we are faced with the reality that we may have to resolve or ignore our differences and come together if we want to prevent the apocalypse, just like in Independence Day.